Since completing his Full Mine Diver course in 2019, Jon Glanfield has practically taken up residence in Aberlas with dives on an almost weekly basis. His visits turned from simple dive experience to begining a huge task of surveying the mine and it’s contents. We caught up with Jon and he kindly submitted the following article on the subject.

As some members will know, we have recently started what we are calling a “survey” in Aberlas – but whether we will do justice to this description, given the ground to cover, will remain to be seen.

Partly the idea was an add-on or pre-cursor to Ian France’s detailed archaeological review of artefacts, partly it emerged from the boredom of Lockdown and too many mouth-watering podcasts and You Tube interviews from the globe and partly a genuine interest in documenting, recording and imaging the incredible range and diversity of artefacts in the mine.

Following my Full Mine Diver course I had concentrated a reasonable amount of time in Aberlas, simply refining, practicing and becoming familiar with the dark environment generally. Gradually though as a greater appreciation of the history, cachet and beauty of the mine grew on me it became clear that although true exploration had been played out in the tunnels, there was still a lot of potential for objective based dives.

The basic haulage ways stretch over 900m alone and with circa 28 chambers on the shallow side and 7 on the deep, the actual area is staggering.

Most is lined but some still aren’t and artefacts range from the solid support infrastructure of rails, pipework, points indicators and incline engineering, to laden carts, empty carts, smashed and crushed carts, sections of timber doorways, batteries, fragments of explosive boxes, boots, tools and even batteries.

However, when I started, there was no easy way to plan a dive based on target artefacts, no distance markers to verify location in the mine and only a smattering of information on jump arrows about the corresponding chamber.

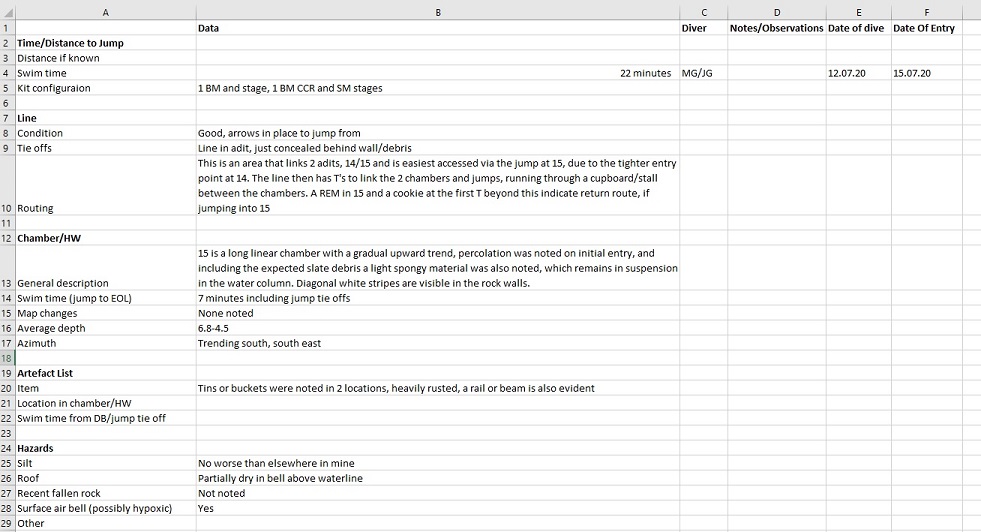

Given its layout and reasonable quality of mapping, there were some clear steps to take in order to kick things off, annotate the map to permit collective identification of location, install distance markers for reference and collate a list of data to collect for future reference.

We see this as very much organic, in as much as the methodology, data, approach etc. is available for constant review, evaluation and improvement. When I researched the subject, very little consensus exists in terms of mine surveying, given that the usual tenets of cave survey are largely known in terms of depth, direction, azimuth etc. due to their man-made origin.

To this end we are very much making up as we go and any improvements or suggestions would be warmly welcomed and implemented.

The idea is to make it accessible to all, so if you make a dive and want to record only time and distance for future reference this is fine, or just document seen artefacts in a given chamber its all very malleable, but at the same time could place a framework around your dive which adds a new dimension.

The hope is that we will also record a list of other objectives to improve the environment, such as the distance markers, chamber labelled jumps, line repairs and improvements, lines in unlined spaces etc.

Longer term this should hopefully become a resource for those not so local to plan a dive based on what they want to see, similar to a wreck tour from Divernet perhaps.

It’s open to all, and there’s a hell of a lot to cover, so please do let me know if you want to get stuck in at whatever level – eventually we hope to use the mistakes to inform similar projects at other venues, simultaneously so that we can become more 3 dimensional and avoid boredom by over diving one location.

Author, Jon Glanfield